Walk into any grocery store in the English-speaking world, pick up a packaged food item, and you will see the same footnote: “Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000 calorie diet.”

But who is this mythical person who requires exactly 2,000 calories?

Is it the 6-foot-tall construction worker in Chicago? The petite office manager in London? The marathon runner in Vancouver? The reality is that the “2,000 calorie” standard is a rough average derived from surveys in the late 20th century. Relying on it for your personal health goals in 2025 is like wearing a “one-size-fits-all” shoe—it might cover your foot, but it probably won’t help you run.

Understanding your caloric needs is the bedrock of nutritional literacy. Whether your goal is to shed stubborn body fat, build lean muscle, or simply maintain your energy levels through a chaotic work week, the math matters. This article moves beyond generic guidelines to explore the physiology of energy expenditure. We will dissect the components of your metabolism, provide the tools to calculate your specific number, and explain why “calories in vs. calories out” is both true and remarkably complex.

1. Anatomy of a Calorie: Breaking Down TDEE

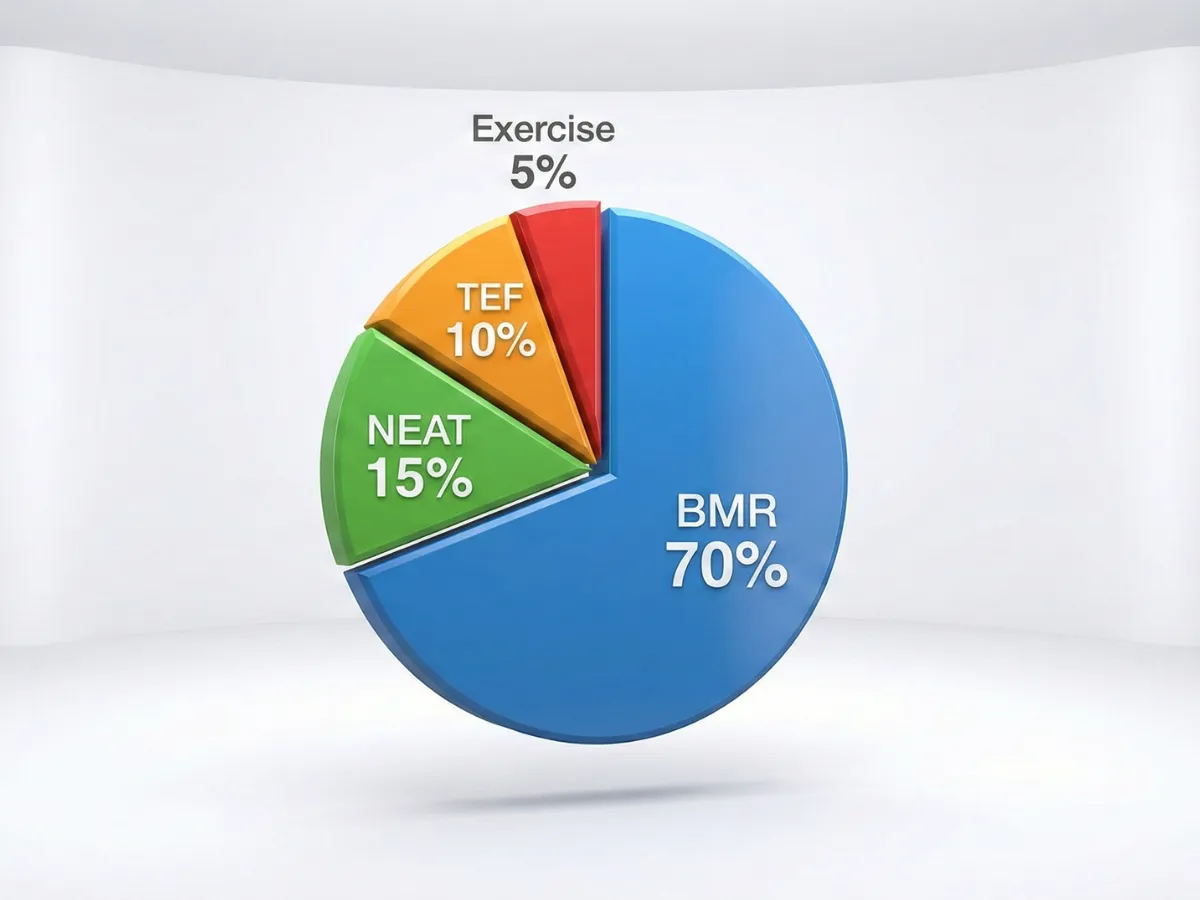

To understand how much you need to eat, you must first understand how you burn energy. Your daily burn is not just what you see on your smartwatch after a run. It is a sum of four distinct parts, collectively known as Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE).

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) – ~60-70%

This is the energy your body needs just to keep the lights on. If you laid in bed all day without moving, thinking, or digesting, you would still burn these calories. They fuel your heart beat, lung function, and cell production.

-

The Driver: BMR is largely determined by your body size and composition. Muscle tissue is metabolically expensive; fat tissue is not. This is why two people of the same weight can have vastly different BMRs if one is muscular and the other is not.

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) – ~15-20%

This is the hidden variable. NEAT includes all physical movement that is not deliberate exercise. It is fidgeting, walking to the copier, typing, cooking, and standing.

-

The Impact: NEAT varies wildly between individuals. A waiter constantly on their feet might burn 800 calories of NEAT, while a software engineer might burn only 200. This variance often explains why some people seem to eat whatever they want without gaining weight.

Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) – ~10%

Digestion is work. Your body burns calories to process the food you eat.

-

Protein Power: Protein has a high TEF (20-30%), meaning your body burns significantly more energy digesting chicken than it does digesting pasta (which has a TEF of roughly 5-10%). This is a metabolic advantage of high-protein diets.

Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT) – ~5%

Surprisingly, formal exercise usually contributes the least to your total daily burn. A 30-minute jog might burn 300 calories, a fraction of the 2,000+ you burn just existing (BMR) and moving around (NEAT).

2. The Math: Calculating Your Number

While laboratory testing (calorimetry) is the only 100% accurate method, mathematical formulas get us close enough for practical use. In 2025, the Mifflin-St Jeor Equation remains the gold standard for accuracy in clinical settings.

Step 1: Calculate BMR

Use the following inputs for the calculation (Weight in kg, Height in cm, Age in years):

-

For Men: (10 × weight) + (6.25 × height) – (5 × age) + 5

-

For Women: (10 × weight) + (6.25 × height) – (5 × age) – 161

Narrative Example: Let’s take “Sarah,” a 35-year-old female, 165cm tall, weighing 70kg.

(10 × 70) = 700

(6.25 × 165) = 1,031

(5 × 35) = 175

Calculation: 700 + 1,031 – 175 – 161 = 1,395 Calories.

This 1,395 is her Coma Calories. If she eats only this amount, she will likely lose weight, but she will also feel lethargic because she isn’t fueling her movement.

Step 2: Apply the Activity Multiplier

Now, multiply that BMR by an activity factor to find the TDEE. Be honest—most people overestimate their activity level.

| Lifestyle | Description | Multiplier |

| Sedentary | Desk job, little to no exercise | BMR x 1.2 |

| Lightly Active | Light exercise 1-3 days/week | BMR x 1.375 |

| Moderately Active | Moderate exercise 3-5 days/week | BMR x 1.55 |

| Very Active | Hard exercise 6-7 days/week | BMR x 1.725 |

| Super Active | Physical job + training | BMR x 1.9 |

If Sarah works a desk job but goes to yoga twice a week, she is “Lightly Active.”

1,395 (BMR) × 1.375 = ~1,918 Calories (TDEE). This is her maintenance number.

3. Adjusting for Goals: Weight Loss vs. Muscle Gain

Once you have your maintenance number (TDEE), you adjust it based on your goal. This is where the art meets the science.

The Fat Loss Zone (The Deficit)

To lose fat, you must consume fewer calories than your TDEE. However, more is not better.

-

The Safe Deficit: Aim for 15-20% below maintenance. For Sarah (TDEE 1,918), a 20% deficit is roughly 380 calories. Her target becomes 1,538 calories.

-

The Danger of “Crash Dieting”: If Sarah drops to 1,000 calories (a 50% deficit), her body perceives a famine. It responds by lowering her BMR (burning less energy at rest) and increasing ghrelin (hunger signals). This is “metabolic adaptation,” and it is the primary reason for rebound weight gain.

The Muscle Building Zone (The Surplus)

You cannot build a house without extra bricks. To build muscle, you generally need a caloric surplus.

-

The Lean Bulk: You don’t need a massive surplus. 250–500 calories above maintenance is sufficient. Any more than that will likely be stored as fat, not muscle.

-

The Protein Requirement: In a surplus, protein intake must be high (1.6g to 2.2g per kg of body weight) to direct those extra calories into muscle synthesis rather than fat storage.

4. Why the Calculators Might Be Wrong

You followed the formula, you tracked your food, but the scale isn’t moving. Why? Because calculators are static, but your metabolism is dynamic.

The Tracking Error

Research consistently shows that humans underestimate their calorie intake by 20% to 50%.

-

Sauces and Oils: That tablespoon of olive oil you used to sauté the veggies? That’s 120 calories often left untracked.

-

Licking the Spoon: Tasting food while cooking adds up.

-

Inaccurate Labels: FDA regulations allow food labels a margin of error of up to 20%.

The Adaptation Factor

As you lose weight, you become smaller. A smaller body requires less energy to move. If Sarah loses 10kg, her BMR drops. She cannot keep eating 1,538 calories and expect the same rate of weight loss. She must recalculate her needs periodically.

The Hormonal Environment

Calories are the primary driver, but hormones are the traffic controllers.

-

Cortisol: Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which can lead to water retention (masking fat loss) and insulin resistance.

-

Hypothyroidism: An underactive thyroid lowers BMR significantly, making standard calculators inaccurate (overestimating needs).

5. Quality vs. Quantity: Do Calories Matter If I Eat Clean?

A common debate in nutrition circles: “If I eat 2,000 calories of donuts vs. 2,000 calories of salmon and rice, is it the same?”

Thermodynamically, yes. In a sealed chamber, they release the same heat energy.

Physiologically, no.

-

Satiety: The salmon and rice will keep you full for 5 hours. The donuts will leave you hungry in 45 minutes, leading to overconsumption later.

-

Hormonal Response: The donuts spike insulin, promoting fat storage and crashing energy. The salmon provides amino acids for repair and stable glucose.

-

TEF: As mentioned earlier, the body burns more calories processing the protein in the salmon than the sugar in the donuts.

Therefore, while quantity determines your weight (you can technically lose weight eating only junk food if you restrict calories enough), quality determines your body composition, health markers, and how you feel.

Conclusion: Listen to the Data, But Trust the Body

Calculating your daily calorie needs is not an exact science; it is an estimation game. The Mifflin-St Jeor equation gives you a starting point, not a commandment.

The most effective way to determine your true needs is empirical testing.

-

Calculate your estimated TDEE.

-

Eat that amount for two weeks.

-

Track your weight daily and take an average.

-

Analyze: If your average weight stayed the same, your calculation was correct. If it went up, your TDEE is lower than calculated. If it went down, your TDEE is higher.

In 2025, with apps and wearables, we have more data than ever. But the most important data comes from your own biofeedback. Are you energetic? are you recovering from workouts? Are you sleeping well? If the answer is no, you likely aren’t eating enough, regardless of what the calculator says.

Your Next Step:

Use the formula in Section 2 right now. Calculate your BMR and TDEE. Then, download a food tracking app for just three days. Don’t change your diet yet—just log it. Compare your actual intake to your calculated number. The difference might surprise you.

FAQs

1. Is 1,200 calories enough for a woman?

For most adult women, no. 1,200 calories is often near the BMR of a small, sedentary woman. Eating at this level leaves little room for nutrients and can downregulate metabolism. It is generally appropriate only for short, petite, sedentary women looking for weight loss, and usually not for long periods.

2. Does muscle really burn that many more calories than fat?

Yes, but don’t exaggerate it. Muscle burns about 6 calories per pound per day at rest, while fat burns about 2 calories. However, the real value of muscle is that it allows you to train harder (burning more EAT) and creates a “glucose sink” for the carbohydrates you eat.

3. Should I eat back the calories I burn exercising?

Generally, no. Fitness trackers often overestimate calorie burns by 20-30%.14 If your watch says you burned 500 calories, and you eat an extra 500, you are likely erasing your deficit. A safer bet is to eat back 50% of what the tracker claims, or stick to your TDEE activity multiplier.

4. What is “Starvation Mode”?

“Starvation mode” is a colloquial term for adaptive thermogenesis. Your body doesn’t “hold onto fat” in a deficit; it just becomes ultra-efficient at using energy. Weight loss slows down, but it does not stop completely unless you are truly starving (single-digit body fat).

5. How do I know if I have a slow metabolism?

True metabolic damage is rare. Most cases of “slow metabolism” are actually a result of low NEAT (not moving enough outside the gym) or underestimating calorie intake. However, issues like hypothyroidism or PCOS can lower BMR and should be ruled out by a doctor.

References

-

Mayo Clinic – Calorie Calculator: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/weight-loss/in-depth/calorie-calculator/itt-20402304

- Harvard Health – Calorie Counting Made Easy: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/calorie-counting-made-easy

-

PubMed – The Mifflin-St Jeor Equation Reliability (Systematic Review): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15883556/

-

Scientific American – The Science of Calories: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/science-reveals-why-calorie-counts-are-all-wrong/